- Simon and Garfunkel, “America” (1968)

- Merle Haggard, “The Fightin’ Side of Me” (1969)

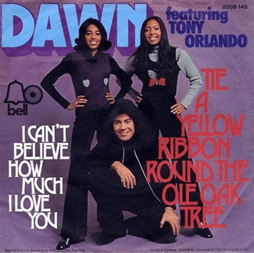

- Tony Orlando and Dawn, “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Old Oak Tree” (1973)

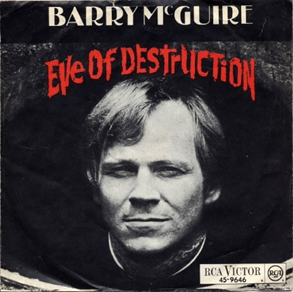

- Barry McGuire, “Eve of Destruction” (1965)

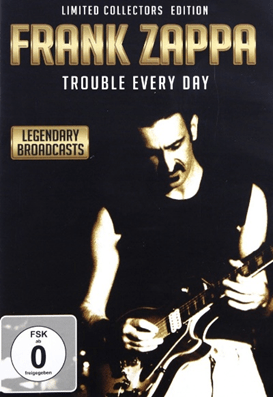

- Frank Zappa, “Trouble Every Day” (1996)

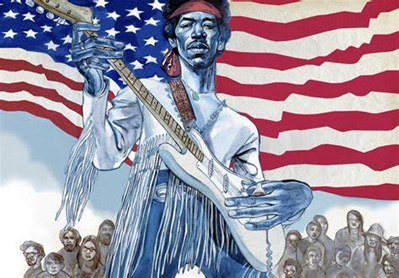

- Jimi Hendrix, “Star Spangled Banner” (1969)

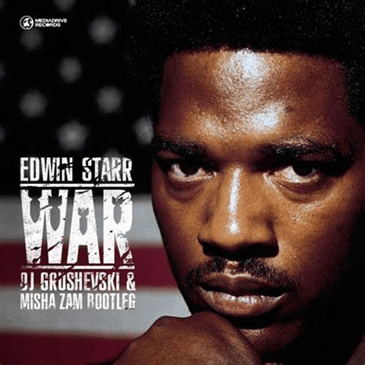

- Edwin Starr, “War” (1970)

- Gil Scott-Heron, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” (1971)

- Loretta Lynn, “The Pill” (1975)

Simon and Garfunkel, “America” (1968)

Arguably both hymn and protest, Simon and Garfunkel’s “America” is a civil anthem written in an era in which the conception of the American identity was in flux. The song is a narrative poem set to music, telling the story of a young man who hitchhikes from Saginaw, Michigan, to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to take a Greyhound bus with his paramour Kathy in search of America. It is difficult to hear a song from the late 1960s about a tour of America by a Greyhound bus without thinking of the role of Greyhound and mixed-race groups of Freedom Riders traveling to the American South to fight segregation and work to protect African-American voting rights. Ultimately, “America” is a civil anthem that does not serve to define what America is; rather, it is a song that defines America as a location wrenched from its historical moorings. It is a song about a man in search of what America is at a time when America was changing.

Merle Haggard, “The Fightin’ Side of Me” (1969)

This theme of a changing America (and the fear thereof) is reflected in “The Fightin’ Side of Me”, the title track to Merle Haggard’s 1969 release, which was released two years after the “summer of love” at the height of protest movements in the US. The song is arguably the first “America—love it or leave it” anthems, particularly in the Country genre. Teachers can use this song as a means of reminding students that America was truly divided at this time—those supporting our foreign interventions and those opposing them. Teachers would be able to explore the justifications for Viet Nam, for example, or segregation/Jim Crow. It would also allow teachers an opportunity to use the past as a means of framing the present, examining the national divide(s) made clear by the 2016 presidential election.

Tony Orlando and Dawn, “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Old Oak Tree” (1973)

Taking a less direct approach to supporting the US, “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Old Oak Tree” by Dawn featuring Tony Orlando (1973) eschews the critical musical commentary that surrounded the Vietnam War. Instead, it focuses on a simple love story between two characters, a male soldier fighting in Southeast Asia and his girlfriend back home. Our protagonist wants to know whether his girlfriend back home is still interested in him and, in a letter, he asks her to “tie a yellow ribbon” around an oak tree if she wants to continue their relationship; at the end of the song, the returning more solid sees a tree filled with yellow ribbons. “Tie a Yellow Ribbon” truly stood out at the time for its positive characterization of a soldier’s life in a period when many returning servicemen were greeted not nearly as warmly. Beyond just the rather simplistic narrative, “Tie a Yellow Ribbon” forces students to consider what society owes to those returning men and women who served in the military.

Barry McGuire, “Eve of Destruction” (1965)

To explore the way that protest anthems function as a means of constructing American identity, Barry McGuire’s “Eve of Destruction” (1965) provides rich material for the classroom. It contains opportunities for classroom discussion of the ratification of the Twenty-Sixth Amendment, The Civil Rights movement, The Space Race, The arms race, and, of course, the Vietnam War. The song was savaged in some quarters for its “anti-American” attitude, enduring charges that it provided fodder for the communists to impugn Americanism, and provoked several reaction songs countering its lyrics which could also be introduced. A classroom examination of “Eve of Destruction” provides an opportunity to explore how the counter-culture movements of the 1960s impacted the construction of American identity in the second half of the 20th century.

Frank Zappa, “Trouble Every Day” (1996)

Of course, sometimes the counterculture stimulated a counter-response that did not come from the mainstream. After watching The Watts Riots on television Frank Zappa composed “Trouble Every Day”, recorded in 1966 by his band the Mothers of Invention on their debut Album Freak Out. The lyrics are equal opportunity indictments of the “mass stupidity” of the rioters, television journalists, racist/conformist Americans, and those who believe in the American Dream. Teachers can use the song to explore just about any issue that divided the nation in the period; it also predicts American fascination with the 24-hour news cycle and sensationalism in the media. Zappa makes reference to the failure of the Great Society; the song is a great way to introduce a debate on its success.

Jimi Hendrix, “Star Spangled Banner” (1969)

Jimi Hendrix’s 1969 treatment of the National Anthem from Woodstock, one tinged with distortion, spoke to a level of mistrust, if not disgust, that many Americans felt about their country at the time. Certainly, his was not the first version that was purely instrumental. But the amount of left turns and surprises Hendrix could evoke from his guitar created a postmodern pastiche of what was previously a staid tune. The result is a performance that Hendrix described as “beautiful” while critics saw nothing less than the desecration of the National Anthem. His multiracial status—African American and Native American—invited much white hatred towards this performance as well. Pedagogically, Hendrix’s rendition asks a social/aesthetic question: what social values emerge from non-traditional performances of traditional anthems?

Edwin Starr, “War” (1970)

In an era in which anti-war protest songs were legion, Edwin Starr’s “War” stood out in interesting ways. The song was recorded on Motown Records, a label that actively tried to avoid protest music in the interests of maximizing profits by appealing to middle-of-the-road audiences whose influence largely determined radio airplay. The explosive lyrics of the song are certainly an excellent angle for exploring anti-war protests during the US involvement in Vietnam. Beyond that, though, the song has a special resonance when coming from an African-American voice and represents a unique opportunity to broach discussions of the disproportionate burden placed on minority groups to fill the enlisted ranks during the draft and the uses of non-violent means by African Americans to promote social change. The song also provides an opportunity to explore the ways that economic pressures often dampen social protest—particularly in minority communities.

Gil Scott-Heron, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” (1971)

Gil Scott-Heron’s 1971 jazz-influenced spoken word “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” blends lyrical anger with musical restraint. Scott-Heron contrasts the reality of black existence while name-checking Richard Nixon, Spiro Agnew, and other figureheads that represented to him white apathy to blacks’ suffering. Scott-Heron also takes aim at rampant consumerism that, intentionally or not, obfuscated blacks’ daily experiences to a wider, whiter, public. This multifaceted message has resonated across generations; teachers may want to compare Scott-Heron’s original song with those later treatments and discuss which elements later artists sought to emphasize more and which seemed less relevant to them.

Loretta Lynn, “The Pill” (1975)

Tame by today’s standards but highly controversial at the time, Loretta Lynn’s “The Pill”, released in 1975 was about a woman being happy she could control her own body and stop getting pregnant if she wished. While many country radio stations banned the song, the controversy ultimately helped its success; it peaked at #5 on the Billboard country chart and would cross over to the Hot 100 in the US and hit #1 in Canada. Teachers could use the song to discuss the women’s rights movement writ large; likewise, the song is fodder to discuss the convoluted movement of the Equal Rights Amendment (passed in 1972, but failed ratification by 1979) as an example of how to amend the constitution. Finally, older students would be able to use the song as entrée to discuss birth control as a means of female empowerment including the highly controversial 1973 Roe v. Wade decision.