As the authors moved forward with the project, they realized that there needed to be boundaries and definitions under which they operated. The first understanding that had to be operationalized was what is meant by producing good citizens. For the purposes of this article, the authors wish to use the concept put forth by Joel Westheimer and Joseph Kahne who define good citizens as those ready to become active participants in a participatory democracy, versus members of a procedural democracy. Westheimer and Kahne make the distinction as such: citizens in a procedural democracy “maintain the right to vote and take part” while citizens in a participatory democracy not only take part in voting but “work collectively toward a better society” (2).

Once the concept of the kinds of citizenship in a democracy is operationalized, the boundaries of the playlist must be established. The proposed playlist is neither intended to be absolute nor final. For starters, the three authors purposefully allowed themselves three songs for the periods later delineated; the selections are intended to show a balance between patriotism and protest as both are integral to the civil religion. When setting the criteria for inclusion, the authors considered the multivariate definitions of the following terms. For the purposes of this article, the authors use the following:

That which reflects the beliefs, language, norms and mores of the group which holds and wields the greatest power in a society. In the second half of US history, dominant culture was essentially that of hetero, Protestant, abled, middle class white men.

As Raymond Betts explains, with the emergence of brand recognition during the interwar period came the understanding that there was “a quantitative effect on quality”. Numbers added up to a qualitatively different social and cultural environment”. For the purposes of this article, the authors define mass culture as things that are produced in a society to appeal to/be consumed by the dominant culture. While these are consumed by the dominant culture, that does not mean they are valued by the dominant culture; indeed, because of their popularity, items of mass culture are often discounted. As Marshall Fishwick describes, as American mass culture in particular spreads across the globe, “intellectuals see mass culture, and not religion, as the opiate of the people” while “ordinary people, on the other hand, find all these things fascinating and irresistible”.

Fishwick claims that popular culture cannot be defined literally any more but only “metaphorically—a wandering minstrel, a thing of shreds and patches”, and Betts argues that “contemporary popular culture is almost without definition, so all-embracing are its subjects, so far are its effects”. However, for the sake of this article, the authors operationalize popular culture as things which are consumed, whether produced as part of mass culture or outside of it, which become popularized among any cultural group in a society.

Both mass and popular culture are tools of propaganda; however, this has evolved over time. As Alex Edelstein notes, the interwar period through the early 20th century generated “old propaganda” which was “linked to the control and manipulation of mass cultures” in which “charismatic leaders directed propaganda to mass publics and mass media amplified those messages.” However, starting after World War II, mass culture evolved into popular culture, a “new propaganda” which was the “product of the more egalitarian, participant forces” in which members of society through music, writing, and performance, they have been creating means to permit their participation in the popular culture”.

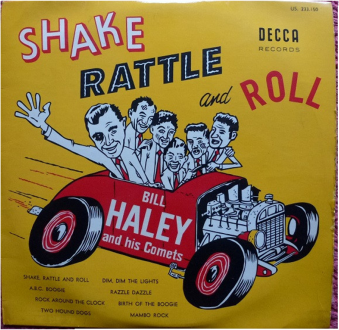

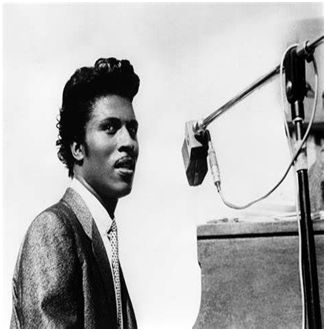

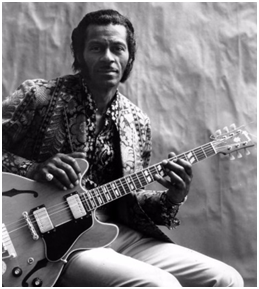

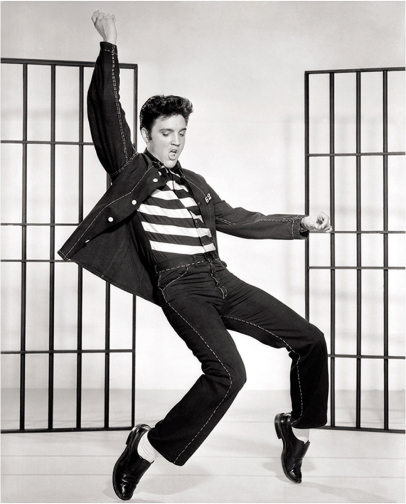

As the authors assembled their playlist, it became apparent how influenced by mass culture they themselves were: three highly educated, cis-gendered men from suburban/middle class backgrounds raised in Protestant faiths tended to choose songs recorded by people who shared their social identity. They recognized that just as voices of marginalized peoples need to be infused throughout curricula rather than inserted in tokenistic, “sidebar” approaches, so too did they need to ensure that marginalized voices were included in the playlist. This is particularly relevant in the study of popular music as so often the voices of marginalized become co-opted (and often sanitized) by dominant culture: Big Joe Turner recorded the penultimate version of “Shake, Rattle and Roll ”, but it was Bill Haley and the Comets that took their version to number one on the charts. Fats Domino, Little Richard, and Chuck Berry recorded the first rock and roll songs, but Elvis Presley is considered the father (and king) of rock and roll.

Another criterion that was of importance to our choices was teach-ability: all songs had to be pedagogically meaningful lyrically and/or contextually to give teachers tools for their classrooms. As we present the playlist, we also share pedagogical possibilities or discussion starters for each song.

As we workshopped the playlist, the notion of popularity within mass culture arose frequently. Our selections are part of mass culture—they were all produced and released for the general public. In many cases, the songs have been incorporated fully into the civil religion due to their popularity; however, popularity was not a criterion for inclusion. We admit that some of our songs are a bit obscure, and others overshadowed by more popular songs by the same artist/ on the same album. Teachability and thematic connection to the civil religion trumped popularity: thus some of the biggest artists of the 20th century are not on this list.

Next, the authors wanted to be sure that the dual nature of music was reflected in the songs they selected, striving to find songs that were seen as patriotic as well as those protesting.

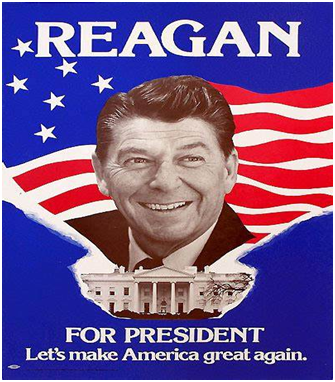

The authors also fully recognize that depending on the context, songs can be considered multi-contextually. The most illustrative example of this is Bruce Springsteen’s 1984 “Born in the USA”. Adopted by the Ronald Reagan campaign when it was released, many considered it to be a patriotic anthem; it is only with time and lyrical analysis that the protest nature of the song becomes apparent, as exemplified by Glenn Beck’s calling for its boycott in 2010 because he considered it anti-American.

The question of the use of civic hymns as propaganda must be addressed. At the time of this writing, the dissemination of government propaganda via social media is particularly relevant across the political spectrum. As such, Edelstein’s philosophical distinction must be remembered:

A broadly participant popular culture with its bedrock of First Amendment rights, knowledge, egalitarianism, and access to communication is the bedrock of democracy, and the breeding grounds of the new propaganda, whereas a narrow participant, uninformed, and hierarchical mass culture, in which only a few speak to many, recreates the context of the old propaganda (5).

Are civic hymns, as defined by this article, examples of propaganda? Arguably yes, but propaganda for multiple sides of any issue. If educators truly want active participants in our democracy, they need to encourage all voices, whether stirring in support or defiance and present students with models thereof. As Neil Postman cautioned, when educators play it too safe with their content it proves counterproductive to making active citizens.

The strict application of nurturing and protective attitudes towards children has created a paradoxical situation in which protection has come to mean excluding the young from meaningful involvement in their own communities. It is hardly utopian to try to invent forms of youthful participation in social reconstruction as an alternative or supplement to the schooling process. Civic hymns are one means to provide students an arena to engage in political discourse that is drawn from mass and popular culture. By developing this playlist, as educators we can encourage students to actively engage with exemplars of the variety of politically engaged, often youthful voices in different moments in history.