A Brief History of Youth Culture

Popular music as a vehicle for voices of protest within the civil religion is particularly entwined with the emergence of youth culture in the 20th Century and the concomitant embrace of counter-mass culture narratives in which youth engaged. From the first three decades of the twentieth century emerged an increasingly recognizable youth culture that distinguished young people from adults through dress, morals, and, especially, music. Indeed, jazz is a good exemplar of a genre of music that once marked a form of youthful protest but is now embraced by the mainstream as a uniquely American art form; in that regard, it has moved from protest to patriotism.

Broadly speaking, pre-twentieth-century popular music enjoyed similar levels of enjoyment by adults and young people. Yet unlike 19th-century minstrelsy songs and brass band marches, jazz and its predecessor, ragtime, were understood primarily as dance music, genres that, in the eyes of critics, appealed “purely to the physical” (Hilderbrant 300). Certainly, young people participated in dances such as waltzes and reels in earlier generations, though such steps seemed “staid and conservative” up against ragtime and jazz’s frenetic tempi (Wagner 302).

As Paula Fass noted in her seminal study of 1920s youth culture, “Because popular forms of dancing were intimate and contorting, and the music was rhythmic and throbbing, it called down upon itself all the venom of offended respectability” (301). Nevertheless, or perhaps because of such adult opposition, young dance aficionados sought out almost any opportunity to dance the Black Bottom or the Charleston. One estimate found that 32,000 high school-age students attended movies daily in 1910, while some 86,000 frequented dance halls (Wagner 294).

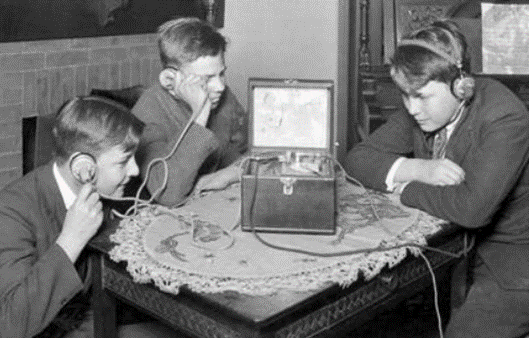

With the advent of commercial radio in 1920 and the prior increasing affordability of phonographs, young people enjoyed increasingly easy access to popular music, much to the consternation of older generations. One high school student wrote in her diary that she was dancing to “damn good jazz” until her parents complained. Her mother turned off the radio, shouting “They call that music!?” (Shrum 104). College students also overwhelmingly embraced jazz’s popular rhythm. One Ohio State student complained, “A college existence without jazz would be like a child’s Christmas without Santa Claus. It would be empty, boresome [sic], unendurable, exasperating. We couldn’t stand it” (“Heaven Protect Jazz!”). Easy, affordable access to music, often listened to outside adult supervision and just as frequently in private as in public places, showed the increasing importance of music as a medium for shaping young people’s perceptions of themselves and their world.

With the rise of youth culture, the history of the twentieth century was, in terms of the cultural artifacts being produced, different from the preceding centuries. In particular, the change in people’s experiences of media shifting from folk culture to popular culture became one of the defining hallmarks of the century. Nearly all scholars agree that the advent of popular culture is a post-industrialist phenomenon. Specifically, “what we call popular culture, for example, a set of generally recognizable artifacts—films, records, clothes, TV programs [sic], modes of transport, etc.—did not emerge in its recognizable contemporary form until the post-Second World War period when new consumer products were designed and manufactured for new consumer markets” (Parker 148). As such, the examination of popular music and its ability to shape civic identities becomes highly fruitful in the second half of the twentieth century.

A Case for Re-Periodizing U.S. History II Classes

There would be a natural tendency among historians to examine shifts in these markets and the sorts of identities they help craft. As a chronicle of the events, history, like time, is continuous, but ever-changing. Indeed, historians “have long been accustomed to identifying and defining these changes by dividing the continuous stream of events into segments” (Le Goff ix). These segments are intended to highlight matters of continuity and discontinuity in the stream of events being chronicled. The act of selecting events to delimit the periods of history “draws our attention to the fact that there is nothing neutral, or innocent, about cutting time up into smaller parts” (Le Goff 2).

In the early 1950s, George Boas, in his examination of artistic periods, argued that historians examining artistic movements share the general desire to divide history into periods. When you are telling the story of a person’s life, he argues, that story is divided into chapters, paragraphs, and sentences. The organization of those periods along certain chronological lines (childhood, adolescence, adulthood, etc.) becomes a natural way of organizing a presentation of the events of a person’s life. What Boas argues, however, is that this is merely an organizational tool. The essential nature of a period, it could be argued, is the cultural and material factors that influence the behavior of people in the period. They are created to give explanatory value to the events of that period (248). A division of historical events into a set of periods, therefore, creates its own focus and emphasis on the events that comprise that period, including the art produced within the period.

movement.

For the sake of this examination of civil hymns, we have chosen our periodization very carefully and deliberately. The most common periodization of the twentieth century by historians uses wars as the markers: World War I, the Interwar Period, World War II, the Postwar, and the Vietnam and Post-Vietnam Eras. This means of dividing the 1900s into periods is not an arbitrary one, but that does not imply that the selection of these touchstones as dividing markers is value-free. These are periods selected because of their usefulness in organizing historical information in a certain way, and, at times, for interpreting the motivations of people acting during those periods.

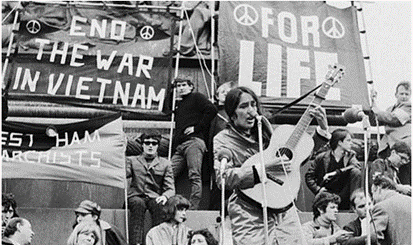

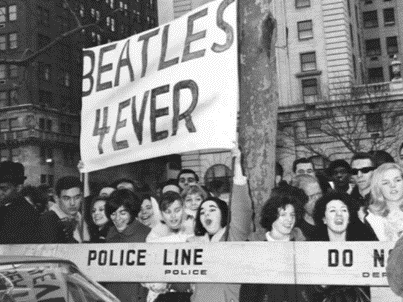

We are not claiming that the way that we have chosen to divide the twentieth century is any less value-free than the commonly used military history model; it does, however, emphasize a different set of defining events in youth culture. This re-periodization is not meant to imply that phenomena that demarcate other ways of periodization are not important. Without a doubt, the Vietnam War, for instance, played a huge role in the youth protests of the 1960s. Arguing, however, for a period beginning with the assassination of John Kennedy and the arrival of the Beatles in the United States and ending with Nixon’s resignation from the Oval Office and the coincident rise of punk rock and hip-hop music focuses attention on different cultural and material factors that influenced the development of popular culture during those intervening years. Some of those factors, like Beatlemania, were a product of youth culture that existed largely independently of military conflict, and the importance of those historical moments may be lost or downplayed when other methods of periodization are used.

Our playlist ends in the early 2000s. Obviously, the events of September 11, 2001, affected the course of geopolitics in the new millennium, including decades-long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The release of iTunes in January of 2001 also heralded a new era of music. As a result, it makes sense for us to end the discussion right at the start of the twenty-first century, as both the music and the way that young people engaged with that music changed quite drastically in the new century. Grunge had died, and traditional methods of delivery of music (LPs, cassettes, CDs, and even, to a degree, radio) had gone with them. As we present the playlists in the following section, we have organized the songs chronologically rather than thematically. If the hope is for students to see the dominant/ mainstream view as well as alternatives to that view, it is better to present the songs side-by-side. Within each time period, however, songs are presented in the order of civic hymns and then protest anthems.