Defining the Civil Religion

To fully engage with the concept of this playlist, teachers should be familiar with the ideas behind the civil religion in the US—and may even want to begin their courses with a discussion of the civil religion in contemporary discourse. Sanford Kessler defines the civil religion as “a religion (or elements of religious belief and practice) that purports to be theocentric, but in fact is designed to serve secular, as opposed to transcendent or otherworldly ends” (7). The concept underlying a civil religion dates back as far as Plato; indeed, as noted by Ronald Weed and John von Heyking, its concepts can be found in Aristotle, Machiavelli, Spinoza, Locke, Pufendorf, Montesquieu, Hume, Kant, Hegel, Smith, Mill, Marx, Weber, and even John Dewey (1-2). Rousseau, so integral to the thought of the founding fathers during the inception of the nation, also provided a blueprint for the civil religion: “Rousseau’s civil religion brings increased political unity to society with a morality that is common enough to overlap with the precepts of most revealed religions and still compatible with the aims of the state” (Weed 159).

As time has passed, there have been many models of the civil religion in the United States. John F. Wilson explains that there are three models of civil religion that must be considered: “a theological model concerned with an ‘American faith’, a ceremonial model concerned with symbolic behavior in society, and a structural-functional model concerned with civil religion as a particular religion within American society” (117). The purpose of the civil religion is to unite, not to divide. As Michael Hughey explores in Civil Religion and Moral Order, “if a social group is to possess solidarity and be enduring”, it must also possess a certain set of rituals and symbols, the meaning of which are societally regulated and passed down from generation to generation. While Hughey makes the case regarding primitive societies, the same is true for all societies: they cannot “endure without some ritual mechanism to rekindle social sentiments in the minds of its members” (55). Indeed, “the unity of society is achieved by evoking similar responses to certain generalized (sacred) symbols in widely dissimilar groups and individuals (that is, ‘all members.’)… Emphasis was placed not on organic interdependence, but on solidarity based on moral consensus and likeness….a mechanical, monolithic symbolic belief system capable of integrating the whole tribe at once” (Hughey 63).

So, what are the underlying virtues of the civil religion that unite us as a people? As seminal thinker Robert Bellah explains, there was a “biting edge” to the civil religion as envisioned by the founding fathers: “Not just general civil religion, but virtue. Not just virtue, but concern for the common good. Not just common good defined in the self-serving way, but the common good under the great objective norms: equality, life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness” (64). It must be noted that Bellah explains that not all founding fathers were fully supportive of this definition of virtue; John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison had different foci.

More explicitly, Peter Gardella argues that in the United States, the civil religion unites its citizens around four values: “Personal freedom (often called liberty), political democracy, world peace, and cultural (including religious, racial, ethnic, and gender) tolerance” (3). He goes on to argue that while some might put free enterprise/ capitalism as integral to the civil religion, the value of capitalism for its own sake has been denied by important contributors to American civil religion” (3). Indeed, the founding fathers saw capitalistic tendencies as being contrary; the civil religion should teach for the public good, while “corruption consists of forgetting oneself ‘in the sole faculty of making money’” (Bellah 62).

Examples of the Civil Religion

When Gardella provided examples of the civil religion, he opened the conversation with elements found in Washington, D.C.: documents such as the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution; buildings, such as the White House and U.S. Capitol; and monuments, such as those dedicated to the Korean War and Abraham Lincoln. However, Gardella also pointed out that elements of the civil religion can be found nationwide: Mount Rushmore, the Statue of Liberty, and Independence Hall in Philadelphia to name a few. Gardella also cites how military sites, such as the Alamo, Gettysburg, and Little Big Horn, become absorbed into the civil religion. We also tend to memorialize sites of great tragedy, such as the Pearl Harbor Memorial in Hawaii and Ground Zero in New York City, as tributes to martyrs to our civil religion (Gardella 2-7).

Beyond documents and monuments, buildings and sites, the formal rites and observances normally associated with a denominational faith must be replicated within a civil religion. As denominationalism has its hierarchy of leaders (bishops, priests, imams, elders, pastors) so too does the civil religion (president, senators, representatives, mayors, councilpersons, alderpersons). Symbols are rampant throughout both denominational religions (cross, hamsa, crucifix, dharmacakra, Star of David, star and crescent) and civil religion (Statue of Liberty, bald eagle, American Flag). As there exist denominational places of worship (churches, synagogues, temples, mosques) so too has civil religion (state capital buildings, town halls, courthouses on all levels). Just as there exist denominational saints, so too do we have those revered in our civil religion. Beyond founding fathers and great presidents, historian John Wilson cites figures “whose roles in the national life may have been less political” such as military figures like General Douglas MacArthur, or even poets such as Walt Whitman or Carl Sandburg (128). Denominational faith has holy days (Christmas, Easter, All Saints Day); civil faith allows holidays (Independence Day, Memorial Day, Thanksgiving). Denominational faith calls for tithing; civil faith taxes. And then there are the hymns.

Civic Hymns

The Denominational faiths have certain hymns that have become canon (“Amazing Grace”, “Hine Ma Tov”, “How Great Thou Art”, Vedas, various charyapadas), songs of worship and guidance for adherents. Over time, many faiths have allowed for an updating and renewing of these songs, from the Renew movement in the Catholicism to the preponderance of worship groups replacing organs in places of worship nationwide. Hymns speak to the tenets of a group’s faith, provide sources of spiritual guidance, and most significantly serve as a primary form of worship.

Our civil religion comes with its own hymns. Of course, the national anthem comes to mind immediately; so too does the song played in every seventh inning of every World Series game since 2001, “God Bless America”. Songs such as “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” and “America the Beautiful” are also important texts to the civil religion. Knowledge of these civic hymns is widespread; most Americans are at least familiar with the songs, if they cannot sing along. The author and one-time radio personality Garrison Keillor, ironically now the subject of protest in his own right, describes it another way. In his editorial “Of thee they sing with feeling”, he describes what happens when crowds at his shows come together to sing various civil hymns:

They felt a naked love of country without anybody telling them to. You don’t get this from wearing a flag pin on your lapel, but when you stand in a crowd and sing about the purple mountains and the buffalo roaming and grace that taught my heart to fear and the Red River Valley, roses loving sunshine, singing in the rain and the bright golden haze in the meadow, it does pull people together no matter how they feel about the Second Amendment.

In addition, just as organized religions update their hymns and music to better meet the needs of the times, so too have our civil religious hymns been updated. As the US has grown and developed as a nation and dealt with the multitudinous social crises in the second half of the 20th Century, our hymns of civic faith updated to fit the times.

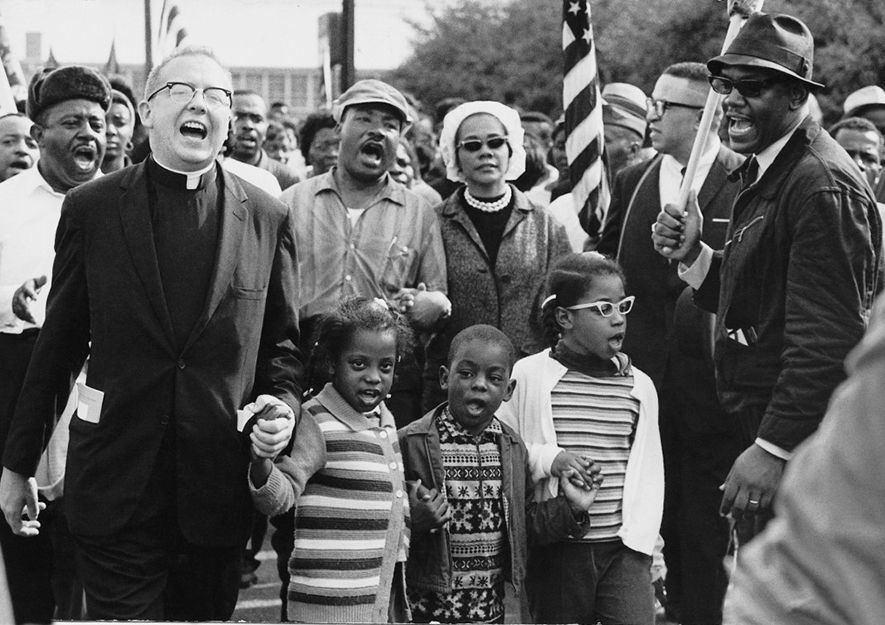

Dissent and Invisibility

However, just as there is no one denominational faith of the United States, adherence to the civil religion is never universal. As Charles Long posits, by definition the civil religion is reflective of the faiths of white European immigrants to the US and thus exclusionary:

“If by “American” we mean the Christian European immigrants and their progeny, then we have overlooked American Indians and American blacks. And if religion is defined as revealed Christianity and its institutions, we have again overlooked much of the religion of American blacks, Amerindians, and the Jewish communities… Indeed, this approach to American religion has rendered the religious reality of non-Europeans to a state of invisibility, and thus the invisibility of non-Europeans in American religious history at this juncture. How are we to understand this invisibility and how are we to deal with it as a creative methodological issue?” (212-213)

Addressing Jones’ questions—how do we understand the invisibility and how do we address it methodologically in this conversation—requires asking whose voices of dissent rise to the top and providing space for those voices to be heard. In the genre of music, this means the conversation must include the voices of cultures marginalized by the mainstream if not co-opted by it.

[1] It must be noted that Bellah explains that not all founding fathers were fully supportive of this definition of virtue; John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison had different foci.