What is the Civil Religion Playlist?

The civil religion playlist is a set of songs for teachers on all levels to use as tools to engage their students in the study of US history and perform political discourse in the hopes of producing active citizens and reclaiming the civil religion for all. This article provides an analysis of two types of civic hymns, protest anthems and patriotic anthems, from a variety of eras across the second half of the twentieth century.

We argue for a reconceptualization of the dichotomy that has arisen and separates the two types of songs: both types of songs should be seen as patriotic. In so doing, we want to simultaneously to uplift the importance of the civic hymn as a means of creating an inclusive conception of what it means to be an American, a grounding condition necessary for the continued functioning of a democratic society, and the importance of the protest anthem in highlighting social injustice and pulling people together to combat that injustice, a necessary precondition to forming a more perfect union. These two types of songs do not lie at opposite ends of a continuum but serve compatible roles in the maintenance of civil society.

How did you choose your songs?

We limited ourselves to one civic hymn and two protest anthems for each period. The criteria for a song’s inclusion included the following:

- The songs had to reflect our democracy, if not encourage active participation in it;

- The songs had to come from mass culture if not popular culture;

- The songs had to include voices of marginalized cultures in more than tokenistic, “sidebar” approaches often taken in history.

- The songs had to be pedagogically meaningful, whether appropriate for a secondary or postsecondary classroom. They had to be teachable, either because the lyrics explored a relevant topic, or the song provided some historical context to the period.

What are the new periods and where are the songs?

Click on the title of each period that follows to take you to the page containing the music from that period.

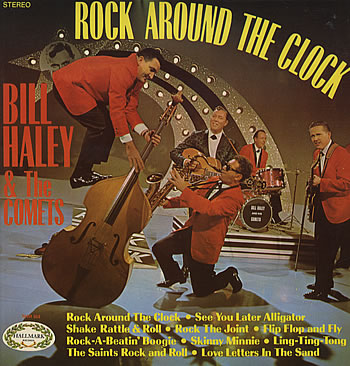

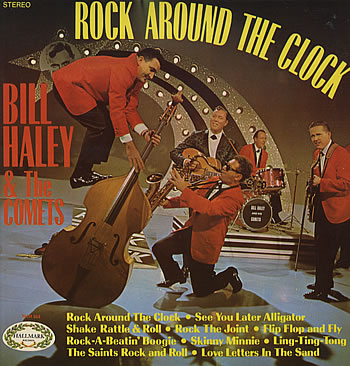

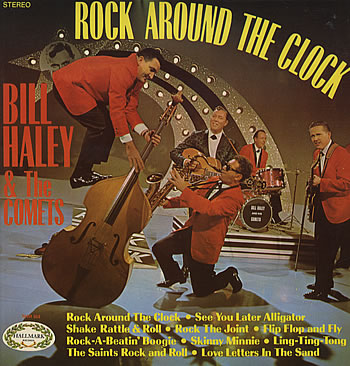

Bill Haley – Beatles (1955-1964)

Bill Haley and the Comets’ “Rock Around the Clock” hit #1 on the Billboard charts on June 29, 1955. It was, of course, after that featured in Blackboard Jungle. Elvis Presley had his first #1 hit (“Heartbreak Hotel”) on May 5, 1956. It was the first of eighteen #1 hits for Presley. Bill Haley and Elvis Presley were repackaging the ground-breaking music of African American artists such as Fats Domino, Little Richard, and Chuck Berry, who

in turn adjusted their own music to popularize it for white audiences. The beginning of the Rock and Roll era, as a consequence, occurred in 1955 and was solidified in 1956. There are certain considerations in terms of the consolidation of corporate music, with the simultaneous burgeoning in the number of music labels (held under umbrella corporations). At the same time, the regionalization of radio station airplay also plays a factor (Lopes 56-71).

in turn adjusted their own music to popularize it for white audiences. The beginning of the Rock and Roll era, as a consequence, occurred in 1955 and was solidified in 1956. There are certain considerations in terms of the consolidation of corporate music, with the simultaneous burgeoning in the number of music labels (held under umbrella corporations). At the same time, the regionalization of radio station airplay also plays a factor (Lopes 56-71).

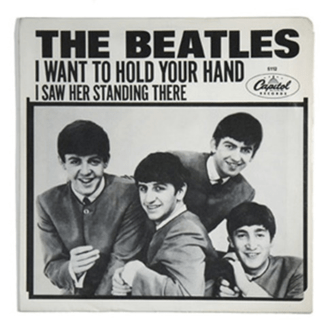

Beatles – Watergate (1964 – 1974)

The second era of post-rock era popular music began at the end of 1963. The assassination of JFK in November of 1963 began a massive cultural shift. This was coupled with the Beatles getting their first #1 hit (“I Want to Hold Your Hand”) in February 1964. The youth culture born of the death of Kennedy and the solace of Beatlemania grew into the youth movements of the 1960s. Women’s voices were increasingly heard in the political arena via the Equal Rights Amendment movement and the rise of feminism, and in popular music, with the rise of girl groups such as the Supremes and singer-songwriters such as Joni Mitchell. This extended to countercultural musical voices such as Nina Simone and Joan Baez as well. Certainly, the music changed after Woodstock in August of 1969 and the Beatles broke up in April of 1970, but the same artists who rose to prominence in the era continued to dominate the musical world through the early 1970s, though they were on “cocaine and caviar autopilot” (Fricke 10).

Nixon – Nirvana (1974-1989)

When Richard Nixon resigned in August of 1974, youth were already experiencing economic difficulties due to the 1973-1975 recession. Also, America ended up leaving Saigon, officially ending the Vietnam War in April of 1975. The punk movement’s scholarship has been fairly well-trod, especially in Dick Hebdige’s book Subculture: The Meaning of Style, Sharon Hannon’s Punks: A Guide to the American Subculture, Ryan Moore’s Sells Like Teen Spirit: Music, Youth Culture, and Social Crisis, and Roger Sabin’s Punk Rock, So What? The Cultural Legacy of Punk. The Ramones formed in early 1974 in Queens, NY, and released their debut album in April of 1976. The Sex Pistols formed in 1975 and released “Anarchy in the UK” in July 1975. Again, the disillusionment with democracy following Watergate, America’s ignominious defeat in Vietnam, and the economic troubles on both sides of the Atlantic ushered in a new musical era. We see in the late 1970s the rise and fall of both punk and disco and the upward trajectory of rap. These were replaced by post-punk, Goth, New Wave, and various strains of heavy metal, not to mention mainstream pop figures like Michael Jackson, Madonna, and Cyndi Lauper, which cultivated a new era of popular music that was becoming increasingly categorized.

As was typical of the Reagan years, we see the experimentation and fragmentations of the late 1970s give way to the corporate influences of the 1980s. As a result of this increased fragmentation, it makes sense to consider the era extending from Watergate into the early 1990s as its own musical period, fueled in part by the rising popularity of MTV, which brought new varieties of music into mainstream America’s living rooms. By the era’s end, hip-hop had entered the mainstream thanks to acts such as Tone-Loc, D.J. Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince, and Young M.C., all of whom had massive success.

Grunge – 9/11 (1989-2001)

In the musical world, there is a strong push against corporate music influences in the early 1990s. Tupac Shakur’s debut solo album, 2Pacalypse Now, released in November of 1991 was also changing the trajectory of rap music, eschewing commercial concerns for politically charged lyrics. Nirvana’s Nevermind album was released on September 21, 1991, and it reached the #1 spot on the Billboard charts in January 1992. This album came right on the tail of Pearl Jam’s Ten, released in August of 1991 which reached #2 on the Billboard charts. It is important to note that the rise in popularity of Nirvana and the rest of the soon-to-be-dubbed “grunge” bands corresponded almost directly with new developments on the internet.

While certain internet technology can be historically traced to the 1960s, the World Wide Web first went public on August 6, 1991 (and would end up giving rise to the Dot Com Boom of the latter half of the decade). Communication technologies ushered in a new technological era, the “Morning in America” optimism of the Reagan era had given way to the cynicism of The Simpsons, the first Iraq War, and the “It’s the Economy, Stupid” Clinton years. In music, the grunge movement borrowed a bleak aesthetic and harsh instrumentation from the 1970s punk playbook and changed the sonic landscape of popular music, signaling an end to some popular musical movements that had been dominant in the previous decade (like the more musically polished hair metal and synth pop). Near the period’s end, Napster’s file-sharing service (which ran from 1999 – 2001) began to shift how people thought about their music.

9/11 – 45 (2001 – 2016)

The tragic events of 9/11 altered the very nature of the US, from the way we board planes to the way we view protest anthems. When the nation invaded Iraq, Country music was ruptured between Toby Keith’s proclamation that putting a boot in someone’s ass is the American way to the Dixie Chicks announcing they were ashamed to be from the same state as President Bush. While there were some protest anthems that emerged in the immediate aftermath, they were often covers of protest anthems from long ago. With the rise of social media and decline of print journalism, the nation’s populace became more divided than ever: the culture wars pervaded most aspects of people’s lives. The period is defined by two presidents representing opposite ends of the political spectrum: from the conservatism and military hawkishness of the Bush era to the hopefulness and progress of the Obama years. This progressiveness was brought to a screeching halt by the election of the nations’ 45th president which gave legitimacy and public value to hate of all forms: white supremacy, sexism, homophobia, religious discrimination. It also gave legitimacy to fringe conspiracy groups, which would have tremendous negative impact in the events of the years to come.

This period saw a major shift in how music was consumed from ownership to streaming. The IPod was first released in October 2001, which shifted people’s music libraries from hard copy to digital and lowered their audio quality expectations in lieu of ease of access. With the increase of availability of high speed internet and rise in ubiquity of mobile phones becoming increasingly pocket computers, people shifted from music ownership to music streaming: Pandora came on the scene in 2005, and Spotify in 2008.

Conclusion: Lasting Influence

Why is the civil religion in the United States important to understand and how long will be of lasting influence? Indeed, as demonstrated by the deplorable level of what passes for contemporary political discourse and rhetoric, isn’t the time to consider the civil religion over? As the United States fades as a global superpower, will also its influence as civil religion? With the new global threats to mankind as a species—the destruction of the environment, extinction of multiple species, terrorism, new forms of totalitarianism—and the increase in nationalistic xenophobia within our borders, why bother focusing on the civil religion in today’s classrooms?

First, as argued by Peter Gardella, United States’ civil religion is drawn from both biblical faith and ancient Roman structures; as they have endured, so too will the influence of the United States civil religion. Gardella writes the United States must face an ending, a fall of the empire or a confrontation with Babylon, an apocalypse. But even if the United States enters a time of declining power, American civil religion will continue, just as the civil religions of England, France, Russia, and Japan have survived declines in power. Even the spirits of ancient Israel and Rome have never really died, but continue to inspire the world. There is nothing in the present situation that should make anyone conclude that American civil religion will sink into irrelevance or be condemned by history. (7)

Second, to further use biblical imagery, just as the New Testament offered a new covenant for the people, so too does examination of the trying times in which we live and work offer an opportunity for a new covenant with the civil religion. In affirming this new covenant, educators need to engage their students in discourse about what is the promise of the civil religion not just in terms of civil rights but civil responsibilities; they need to demonstrate to their students what discourse at its best should be and teach them to reject appeals to the baser nature made by demagogues of all stripes. They need to actively engage their students in civic discourse and civil disagreements. However, the use of civil hymns is disappearing from American schools. As Keillor laments in his editorial:

In years to come, this will be gone. We won’t know the words any more…the common hymns will simply vanish except among us geezers with our ruined voices. Young people will walk around in the bubble of headphones listening to Etaoin & the Shrdlus and their anthems of alienation and wondering why they feel lousy.

This cannot happen; educators of all stripes cannot let this come to pass, we must create opportunities for our students to practice active civic engagement, good citizenship, and meaningful discourse. As George Counts explained in 1952—and still very true today—improving the nation “cannot be accomplished by education alone…Yet it is equally evident that they will never be accomplished without the assistance which organized education can provide.” Everyone involved in education, practitioners to those who prepare them, must recognize that our current moment in time “calls for a great education… liberally and nobly conceived… directed toward the accomplishment of the heavy tasks before us,…that expresses boldly and imaginatively the full promise and the full strength of America in her historical and world setting” (Counts 21). To begin to accomplish this, why not use songs of faith to affirm what makes us great as a nation and songs of protest to patriotically work for social improvement?

Indeed, it seems as if the nation is primed for this. Integral to Joe Biden’s successful campaign for president was rhetoric that used to be the tip of the spear of the right wing culture warriors: pro-America, pro-unity, supporting our democratic institutions. Even those who were not initially receptive to this message during the election became more open to it after watching their temple to liberty defiled by terroristic citizens who revile the message of unity. The civil religion is for everyone; when it becomes partisan, we lose our common ground. It is time to reclaim the discourse inherent within it.

Of course, we would be remiss as authors if we did not end an article calling for a return to debate and discourse without welcoming such ourselves. We enjoyed the conversations and discussions that took place as this article was workshopped in academic conferences and welcome any further discourse on it.